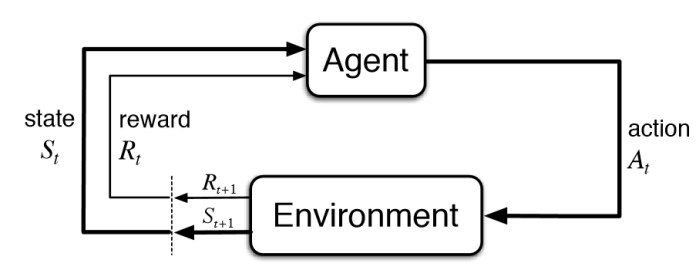

Generally, I come to the conclusions or my learnings from any project at the end of these blog posts but this time, I am tempted (only 50% upset about it) to begin the post by that and here it goes: classic RL alone has a very little chance of being the one bringing us the AI we have been dreaming of (in my humble opinion and limited experience). I’ll get back to why I think so but first, I’ll write some lines about RL. Reinforcement learning is a form of learning where an agent interacts with an environment by taking some action for the state it is in and gets a reward for that action in that state. The ultimate aim is that the agent should learn how to act such that the expected future reward given the current state is maximized. To do that it experiences state takes an action, observes the reward and goes to the next state.

RL agents take a lot of time to learn how to act “optimally” (in some definitions of the word). By time here, I mean that if I put an RL agent in a game vs. a human, the human subject will learn in a time orders of magnitude less than the time the RL agent will take to learn the same thing. The reason I have heard in some talks as to why this happens is that humans operate daily in different environments simultaneously and thus, bring in a lot of their life experiences in the form of priors compared to the RL agent which is learning from scratch. So, we (did this project in a team) decided to design an experiment on this. We thought that let’s train an RL agent on one game and use its learnings as the starting point for another game and if it learns faster, we’ll have something to support the argument above. If it doesn’t, there are multiple reasons as to why it failed. Spoiler alert: it fails!

Various algorithms are out there to teach the RL agent how to learn the optimal action given the current state. Q value, defining this “optimality”, is the expected future reward given the current state and the action i.e. it is a mapping from the state, action pair to a scalar and the job of the RL agent is to learn this mapping. In Deep Q-learning (so 2013!), the classic algorithm of RL, a neural network is used as the policy network which takes as input some function of the current state and spits out the Q values corresponding to different actions that the agent can take. Thus, the agent can simply take the action with the highest Q value for the state-action pair.

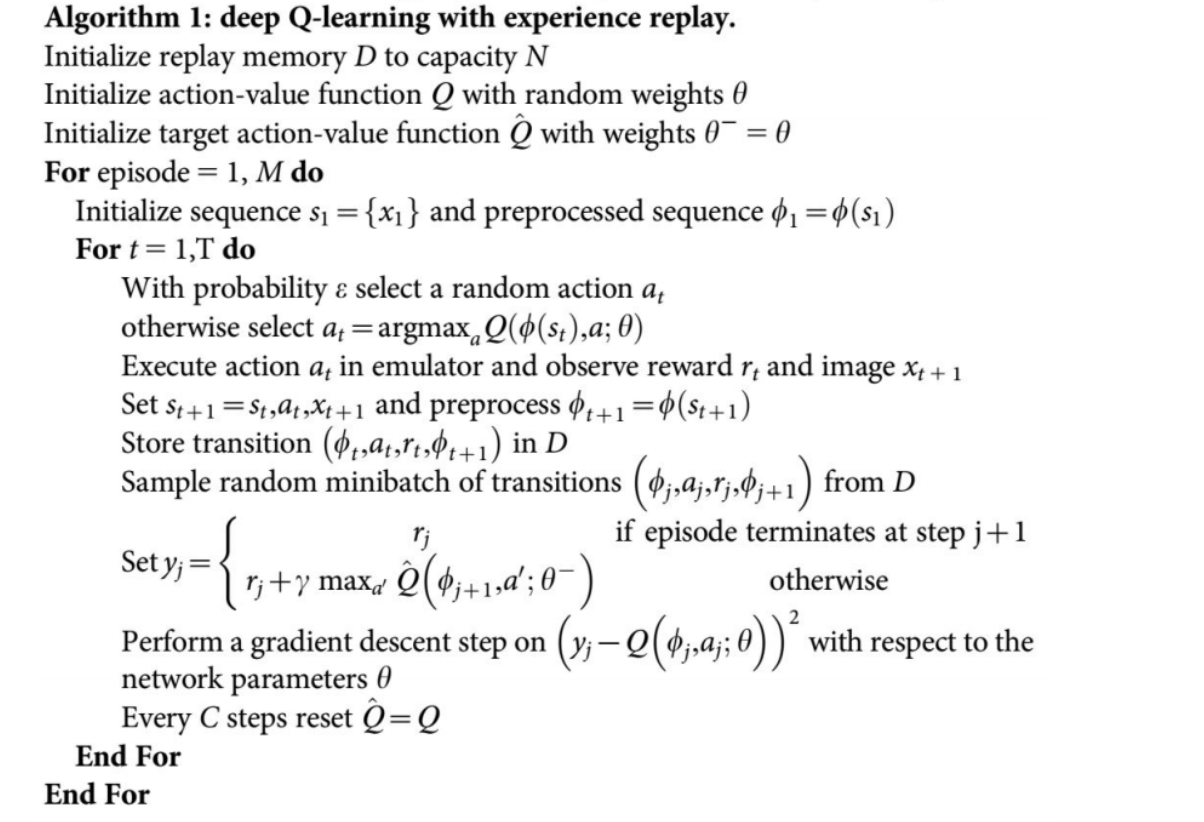

Let’s see if I can concisely explain this algorithm. Experience replay memory stores past experiences of the agent in the environment and the policy network is trained on randomly drawn batches from this memory. The benefit of sampling randomly from experience replay to train the policy network rather than using the most current state is that each experience is used multiple times to train the policy network leading to greater data efficiency. Another benefit is that since the batch is sampled randomly from memory, the experiences in every batch are uncorrelated, reducing the variance of the updates, unlike if recent experiences are used which are highly correlated with each other.

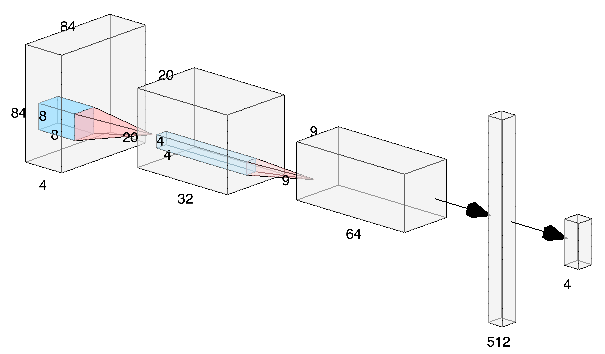

Q value for any state and action pair is given by Q(s,a)=R(s,a)+ Q(s’,a’) where a’ is the action that maximizes the Q value for the next state s’ and R(s,a) is the reward of taking action a in the state s. In this algorithm, we have a policy network (shown below) which is supposedly being trained to learn Q(s,a) and a target network which is a copy of the policy network and estimates the Q(s’,a’). Policy network learning happens by minimizing the Huber loss between Q(s,a) and R(s,a)+ Q(s’,a’). Huber loss is chosen because of the fact that it is convex and differentiable everywhere unlike L1 loss, and doesn’t place a high penalty on outliers like L2 loss. Target network is updated after every few steps to the current weights of the policy network.

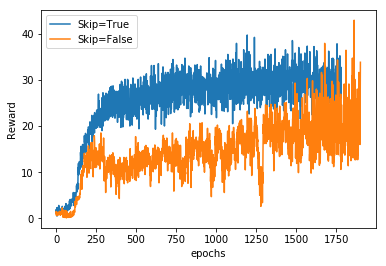

The input to this policy network is a batch of states. Raw input pixels of the game’s screenshot are grayscaled and reshaped to a smaller size to reduce the dimension of the information (getting rid of redundancy) that is in a frame. Each stack consists of 4 such frames and these 4 frames are not from the screenshots taken back to back but each frame here is the snapshot after skipping n number of frames where n is chosen from {2,3,4}. This is done so as to add stochasticity to the learning which makes the agent learn faster and better. The idea behind stacking these frames is that this allows the agent to infer the motion in the game. We tried training the Breakout game with and without the frame skipping strategy. Frame skipping not only increased the learning speed but also the stability of rewards i.e. the variance in the rewards earned in each episode is less in the game where frame skipping is applied, as can be seen from the width of the rewards curve:

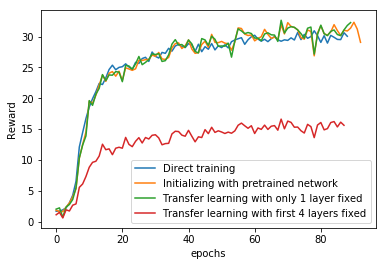

The two environments we chose were Pong and Breakout. We used the OpenAI gym to get the environments for these games. After training on Pong, we used four different training regimes for Breakout: training from scratch, fixing all but last layer weights with the weights of the policy network learned in Pong, initializing all but last layer weights with the weights of the policy network learned in Pong, initializing only the first layer weights with the weights of the policy network learned in Pong. The figure below shows the learning curves:

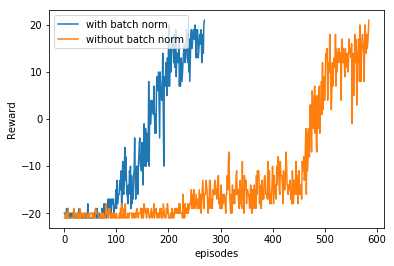

When the agent is allowed to learn only the final layer, it’s performance compared to the other agents is very poor. This is expected because convolutional layers in a CNN learn various feature representations of the inputs based on what depth they occur in the network i.e. the earlier layers learn low-level features of the images (edges, lines, etc) and the convolutional layers later in the network learn high-level features of the images and the high-level features of Pong can’t be directly used in Atari. The learning of all the other agents was comparable i.e. transfer learning or initialization with pre-trained policy network has no effect on the learning of the agent on Breakout game. We also tested the learning on Pong with and without batch norm in the policy network. It only took 330 episodes to reach the maximum score in the game with the batch norm as compared to around 600 episodes if the batch norm wasn’t applied.

Just from observing the time it takes to learn, it is impossible for an RL based AI in a natural setting to try everything to learn. Also, the reward associated with every state-action pair is a scalar which is too less of an information for the complicated states we feed to the network. Also, the scalar reward comes from the environment which is not in the control of the agent i.e. isn’t a part of the policy network and hence, we can’t backpropagate the gradients through the environment. To optimize the policy network, the agent needs to take many actions in order to estimate which action will eventually maximize the reward as the problem here is a discrete optimization (zeroth order optimization) problem which is a lot less efficient than the gradient-based optimization due to no information transfer.

Other than that, I found RL to be too much dependent on the right parameters. As an example, even if the learning rate is changed from 0.0025 to 0.001, the learning abilities of the agent change drastically which isn’t a problem with supervised learning. Personally, I don’t like such sensitive systems. One reason we think why transfer learning didn’t work is that we trained the agent on only one game before testing its performance on another game. We feel that we should have trained it on at least 5-6 games before testing the performance on another game. Also, another method to try can be random sampling from experience replay of n different games together i.e. the agent is trained on multiple games simultaneously and not consecutively which is similar to how humans learn.

Show me the agent playing Pong

Show me the code

Code: GitHub

Teammates: Chinmay and Peeyush

Thanks,

Ashwin